This is concerned with imagery, allegories that are supposed to help understand the path. It is not unusual nor unreasonable to consider the path in this way (the very word path is an image) because what is being described can never be fully described nor can it be fully understood. And at the same time our society as patriarchy at best tolerates the path when there is a willingness to compromise with the path of wisdom but is actively against it when we speak of the path of love.

One spiritual aphorism is that there are many ways up a mountain. But here zandtao wants to examine a more detailed imagery. The Buddha spoke of a raft in the Alagaddupama sutta, and Thay often spoke of a raft. Let me describe a limited interpretation of Thay’s use of raft. The raft is used to cross a river. The intention for the time is to reach the other side, and the other side is not intended as enlightenment or some such completion. But the other side is a place where the journey continues – perhaps without obstacle? Now Thay did speak of this raft as teachings so we cross the river on a raft of teachings, but once on the other side what happens to the raft? Do we carry the raft once we are on the other side? No, for a raft would be a burden on land - a raft of tecahings would be a burden.

Zandtao wants to speak of the river and the raft – and the other side. When he was 23 bill fell into the river of upheaval, and once in the river knew he wanted to get to the other side but he had no raft. Bill did not know there was another side when he fell in, he just knew that this side was a place he didn’t want to be. Once he fell in he was attracted to the other side, and started to swim towards it enjoying the swim. But that joy was cut short as alcohol and conditioning wanted to take him back to the land on this side. But joyous energy was still pushing him towards the other side, and he began to tread water. After a while he began drifting downstream neither having the desire to cross to the other side nor wishing to return to the bank he fell from. Every so often his head would bob up out of the water, and he would catch a glimpse of the other bank reminding him of the desire to reach it but there was no energy and he continued to drift downstream.

After 25 years of treading water and drifting downstream zandtao started to question what he was doing drifting downstream, and he slowly began to think about getting to the other side. At this point he started to gather floating logs (Buddhist teachings) and bind them together as a raft (his practice), and when there was a sufficient raft he was able to get together to the other side. (Apologies for hammering the imagery).

Once he climbed off the raft onto the bank, zandtao had crossed his threshold of autonomy. That was not the end of a journey but in a sense the beginning, a journey in which no raft was needed as he had his autonomy. So he could continue to journey along his path of evolving consciousness – through his writing.

Of this river and raft zandtao could describe Jac as getting on a courageous jetski hammering her way through the torrents of conditioning as she fearlessly reached the other side. This is meant as an amusing compliment. It is certainly a compliment if the time to cross the river matters. Zandtao reached the other side in old age, and is only able to offer the occasional rafts to particular passers-by. Jac has sufficient youth and energy to go out there and encourage people to get on her jetskis.

Even though zandtao treaded water and drifted downstream in his lifetime he was always aware the other side mattered once he had fallen in. On the bank of patriarchy most people are unaware that the other side matters, and when teachers are offering modes of transport to the other side of the river most people are just not interested. They are not happy on their bank but they are surviving within the patriarchy, and they unconsciously accept the message of the patriarchy that there is nothing worth it on the other side. How wrong they are.

When teachers came back to the bank talking of the other side, some people (seekers) decided they wanted to go across; getting across became purpose. Understanding this purpose gave seekers great strength because once they knew of the other side they realised how unhappy they were on this bank of patriarchy. Seekers began to look for transport to cross the river, and this was fraught because many modes of transport were offered and they were unsure what was most suitable for them.

Now the patriarchy knew of the other side, and they were fearful of it because the more people who crossed over the less they had to develop their bank, the less people they had to build up their accumulation in the patriarchy’s bank. So the patriarchy mocked those crossing the river and built up a fear of crossing.

Now the fear was created by the conditioning of the patriarchy but at the same time the fear was created by stories of seekers who had used the wrong form of transport to cross the river and were now afraid to go across. Because the patriarchy wanted to build fear they embellished these stories as that helped build the fear.

For different seekers the river can be an uncrossable torrent at a particular time yet at other times the river can be calm for them – and they can cross. For other seekers choosing the wrong form of transport could be so traumatic that they develop a “fear of flying” or a “fear of the water”, and they then never leave the bank. Jac can cross the river on a jetski but zandtao would never have been able to do that, even though zandtao could admire Jac’s skill on a jetski. What would have happened to bill if he had ever tried to get on a jetski? Would bill have ever got to the other side?

This imagery is the reason zandtao is cautious about Jac’s teachings, and what she has to offer about the other side. He admires the fearlessness and courage – perhaps even a bit envious of the what if for bill, but zandtao also understands that his path was his and that is what it was meant to be – many paths up the mountain, many ways and times across the river, many ways the river flows – torrent or calm. But what matters is getting as many people as possible off this bank of unhappiness and across to the joy on the other side. We need jetskis but not everyone can drive them.

Apologies again for hammering the imagery!!

“You will need courage if you want to be a spiritual rebel …. You will need courage to do things differently. You will need courage to live outside your comfort zone. Your call to action is to go against the ideas you hold about yourself.” Who am I? What are the ideas about myself? These are not asked questions primarily because in the Buddhist learning there was an acceptance of anatta. How much of that acceptance was a belief is a question to be looked at.

To get at this it is best to go back to when the I was formed – the conditioning of bill's upbringing. What zandtao remembers most about what was formed was the fearful bully, he recalls for a significant period of childhood and teens that he was a fearful bully. In the family home what he wanted he took when he could – this meant he took from his younger brother. He could hit his younger brother for some reason without consequences, so he did when he wanted something – zandtao particularly remembers young bill hitting his brother just to get the cat to come and stay in his room. When older, people told him that there was this tendency elsewhere; but mostly for bill it didn’t happen because he was afraid of being hurt and he wasn’t big enough to bully most people. Bill was deeply afraid, and zandtao knows the family conditions that gave bill this fear.

As we grow up conditioning builds up self-esteem, bill had none. He never invested in any of the middle-class conformism central to his family and community, he did enough to get through. Whatever successes bill had never gave him self-esteem because he never invested in it, there was no self-confidence leaving only fear. Neither was he sad, he was just disinterested.

Fear showed itself mostly with women, he was intensely frightened of the few girls he met – hardly meeting any before university, and never having a girlfriend as a teenager. And he avoided situations that required self-confidence. Exam results scraped him into a uni where the fear was overcome through alcohol, with alcohol he met many people including girls but never had a girlfriend because that would require his having a relationship when sober. Over his time at uni a self was built as he grew pride in academic achievement leading to a postgrad year and a good job following from that.

But that was as far as self-esteem took him because he was not interested in his work. However he liked his first job because he was up-west (working in the West End of London), there were interesting people working in the firm, and even though it was drink-related he had a partially-attractive lifestyle “up-west”. And at the weekend he played football with the firm and then drank, all was sorted but going nowhere. However he lacked any discipline, did not connect the need to work with his lifestyle, and was pushed out by the firm. Rather than reacting to the push by working harder his immaturity took him to an awful job in Sevenoaks. And here all the “up-west” had gone, the only time he enjoyed was going back “up-west”. He declined, drink was worse, and he failed at his job. Eventually he did something stupid and deservedly got the sack.

At this point he was still fearful so ran home to parents, but the conditions in the family home were the basis of his problems – as they are with most people. If there was ever courage in this process it was in the decision to return to London without a job. Even though the family home was the wrong place to be bill was still beginning to go through the changes that is now referred to as upheaval – his partial awakening. The one he recalls (already mentioned) is the time outside a pub where there was a Xmas party, he wanted to enjoy such a thing but he knew that such was not for him.

He decided that he had to return to London and get a job. He stepped off the bus at Victoria and went into a nearby employment bureau for a job; with his qualifications in the 70s that was fairly easy and he was sent to Hounslow to do cobol programming. He had some money presumably from parents, stayed in a B&B overnight, found a Chiswick flat the next day, and then began the good stuff of his upheaval. There were jhanas – bells and banjoes, and all kinds of awakening stuff that happened to him. And none of it was part of conscious courage – it just happened.

With this partial awakening that included the end of a good deal of conditioning, there was a rejection of the middle-class conformity he had grown up with. There was no decision, no examination of conditioning or ideals that he held; he simply rejected the conformity of his upbringing.

Fortunately he connected with an Arts centre – reconnected with an Artsy older woman he knew from his first job – somehow. And the Arts people validated all that was in his partial awakening. There was no courage as there was no choice, there was no fear as there was no choice. Fear and lack of courage might have come in later but they were not factors in his partial awakening. Because of this lack of consciousness in his awakening it was easy for zandtao to accept anatta. Because there was low self-esteem it was also easy to see self as ego as attachment, there was no strong self, no self that had self-esteem for bill to cling to. There was no I as personality to analyse and ask “Who am I?”

However with the conditioning of 25-30 years of 2nd childhood where bill gained experience before early retirement there was an I that was conditioned, but undermining any blind acceptance of conditioning was that bill had felt the path and that feeling could not go. During his 2nd childhood he regularly centred on his path to some extent during school holidays, so by the time he developed from his mid-life review it was easy for bill to accept Buddhism – and then easy for bill to accept anatta. In his acceptance of Buddhism there was the development of a meditation practice, he had gravitated towards a practice as part of the review. In the parts of Buddhism that he connected to there was practice.

There was no courage in the awakening process – except perhaps a courage to get on the bus from Manchester to London. In retrospect that might have been courage because “it was not like him”, but in truth he had no choice – stay in the family home? Once connected with the Arts people the path was validated. The power of the upheaval process ran out when he started his PGCE, yet he still felt close to his path at various times after that but that closeness slowly distanced. There was a notion that a Summer holiday in France would begin a world journey doing part-time jobs such as bar work. When he lost his money in St Valery-en-Caux that could have been the start of jobs, but instead he chose teaching – to go back and do the PGCE. That could have been fear but if it was it was not conscious fear – teaching seemed the right decision. In the previous year as a houseparent drinking had become regular, and when he did the PGCE drinking was also regular. Undoubtedly there was fear in that but it was never conscious.

There was never conscious courage in his disidentification. His most powerful disidentification process he calls Nyanga after the place where it happened. It was more than 20 years after his upheaval, and nearly 10 years after he had stopped drinking. Before Nyanga let’s discuss the stopping of drinking, was that courageous? Here is what happened. He got migraines that he associated with stress, and previously had some success with acupuncture and the migraines. They had got particularly bad so he went to this acupuncturist. He treated bill for two or three weeks, and he told him that he was wasting his time as any healing that could come from the treatments he was drinking away. The doctor said don’t come back or stop drinking. It seemed obvious to bill at the time that he should take this opportunity to stop drinking, so he did. The doctor gave him treatments that alleviated some of the withdrawal symptoms, bill drank lots of brewer’s yeast with concentrated orange juice. It was difficult for 6 months but by then he had stopped. When zandtao says bill was an alcoholic many judge that he wasn’t. He was but it was relatively easy to stop because it was the time on his path. With upheaval he had seen the path. When the acupuncturist gave him the ultimatum it seemed the right time; it was the right time but for the path - it was a readiness. It was a huge change in his life as he was drinking between 30 and 40 pints a week but he was holding a job together so perhaps signs of alcoholism weren’t showing. Was the decision courageous? No, it just seemed right. As it was more than 10 years since upheaval maybe there was a conditioned self (from 2nd childhood) but in retrospect zandtao sees the ease of the decision and the discipline to change came from the path - readiness.

With upheaval there was the end of most fear, there was the path, follow the path - why fear? Maybe in the 10-plus years of alcoholism there was some new conditioned self as well, but by the time bill was given the question to stop it just seemed right – no courage.

And Nyanga didn’t have courage either, it came about through wisdom as far as bill can recall. There had been a difficult relationship that finished 7 or 8 years previously, and bill had internalised much pain that had arisen during the relationship. This love had much impact on bill’s life – on the path of his life, circumstances surrounding the relationship were the catalyst that sent him to Botswana. Zandtao recalls that bill thought he was coping with the repression that was UK life but as soon as he set foot onto Gabs airport – with its visible searing heat, he knew a huge change had happened. He was free of the UK, and never had to live there again.

For a number of years after the separation bill thought he was living his life freely. He had thrown himself into politics, and had moved to Botswana when the time came. But after being in Botswana a few years he read about processes like Nyanga, and on his holiday there he decided to do it. There must have been some sort of resistance prior to the night but he cannot recall fear, he cannot recall needing courage to do the process; again it just seemed right to do it - he was just ready.

He was conscious at the time that there was internalised pain from his relationship which in his writings he refers to as Peyton Place – and the woman he loved he calls Peyton. So bill lay down in his holiday bungalow and began the process. From what he read he knew he had to look inside for the pain so he searched inside for Peyton quickly finding her. It was as if there was a pain as a recording there, and when he touched it he replayed that recording. He felt some of the pain again but he felt it in a way that was healing – releasing. It was a powerful release and he cried. He lay there releasing the “recordings” and then looking further for Peyton, and each time he found her he replayed the recording releasing it. This went on through the night until he felt he had released all of his Peyton pain. Was there other pain? And he recalled touching pain concerning his mother but it was OK just to know that and that it wasn’t urgent. He fell asleep for a few hours

The next day he was both drained and revitalised walking around in a kind of daze. He knew that he had been walking around with pain since they had separated but that had now gone; he was more complete – more integrated. It wasn’t however the end of his relationship with Peyton. During his centring summer he met Peyton again (in his mind), there had been no pain since but he had not faced his relationship completely. He could then see that he had loved her – up until that point in his centring summer he had only seen the relationship in terms of pain; from then on despite the pain she put him through that love was important. It was so important to have loved so deeply, and in feeling that depth of love zandtao had moved forward. It was essential to his second childhood to have experienced love, and that loving experience was essential in the writing of Real Love

Zandtao has used this Nyanga process since when he felt there was internalised pain to be released. And what he calls Nyanga is a key process in his Seeker Story.

He never saw that he needed courage to do Nyanga although he recognised there was a level of determination. As he touched the “recordings” there could have been a recoil at the pain, and bill needed not to flee from this recoil. However such fear never came up as his path wanted the release. His path was telling him that Nyanga was a wise process so he did it; he was ready for it. Once he had benefitted from the release there were never doubts and if he wanted to release he went inside and released doing this several times since but never with such a level of internalised “recordings” and release. When zandtao read this from Jac he recalled Nyanga “What makes beliefs stubborn and resistant to change is unresolved trauma held in our bodies. For change to happen in these difficult cases, you will need to face the inner pain by exploring and revisiting your past so that you can heal and free your body from trauma.” Zandtao cannot recall any beliefs associated with his Peyton pain but he loved again briefly after Nyanga and he thinks he was able to love again because of Nyanga. As zandtao explains in Real Love experiencing these romantic loves and being able to love contributed to the deeper and more meaningful spiritual love that he talks of in Real Love.

Teal speaks of a similar approach in her Completion process - "The completion process" by Teal Swan. For zandtao a seeker cannot completely integrate without releasing trauma, as traumas form separate selves or fragments as described in this clip. Psychological integration is part of spiritual integration, and this zandtaomed found with his minimal experience as an elder. Zandtao notes that Nicola Amadora describes herself with a Ph D, and he has a mixed reaction to this. He takes this as Nicola telling us that she sees psychological integration as part of spiritual completion but he is less than ambivalent because of his own academic experience. However if he were mature enough at the time of an awakening, he would seek such training. When an elder is dealing with integration s/he can be dealing with such powerful experiences in a seeker, the more that can be learnt about psychological make-up and the way these experiences can arise from psychological traumas the better he could advise as to spiritual development. But well-being is far from the end of a journey especially as typified by the Google restricted meditation that helps us be wage-slaves rather than being meditation to follow the path.

So “who am I?” and “what ideas do I have about myself?” As zandtao has already said these questions have only been asked in part – and usually within a Buddhist framework. When speaking I is often used but when writing bill, zandtaomed and zandtao are used. It is as if each use of I reinforces the need for I. Bill is used for the time prior to his retirement when studying Buddhism began. Zandtaomed is the name used when advising about meditation, but once he crossed the threshold of autonomy zandtao is used. This threshold introduced a level of questioning that has ultimately led zandtao to separate from the institution of Buddhism. When his autonomy questions it is as zandtao and it is questioning as opposed to helping a seeker build up practice. But what zandtao has learnt concerning love, the feminine way, and Buddhist institutional compromise with patriarchy has necessitated change in his own practice and in what zandtaomed advises. This has also resulted in changes in the Seeker Story that recognise the following:-

But these changes are not asking the seeker to question, zandtaomed helps a seeker build autonomy and then it is for the seeker on their path to question as is their path.

Within Buddhist teachings zandtao does not ask “who am I?” but asks what egos arise as a result of conditioning. From what he understands of anatta the I is a collection of egos that have been built up as part of upbringing within patriarchy so he tries to let them go. If an ego as attachment is recognised then he tries to let it go. As part of his MwB practice step 12 and step 14 focus on such egos. Because of his Buddhist background he see thee attachments arising in 3 ways, through the defilements of greed hatred and delusion (kilesa), through the 4 clingings of desire, ideas, rites and rituals, and clinging to the need for self (known as the 4 upadanas), and the final way is attachment to the khandhas of body, feeling, memories and perceptions and mental processes. So in step 12 he releases the consciousness that attaches to each of these egos, and in steps 15 and 16 uses this consciousness to have greater faith in the path. In step 14 he quenches the dukkha; when we release the fires of attachment there are still embers remaining, step 14 is an attempt to put out the embers as well. Of course this is very much dogma but within this dogma is all the ideas and beliefs Jac asks us to let go.

With each meditation the I is deconstructed although we have to be aware that the conditioning that caused attachment in upbringing is the same conditioning that is around us in adulthood so we have to be aware of the possibility of new egos reformulating a new I.

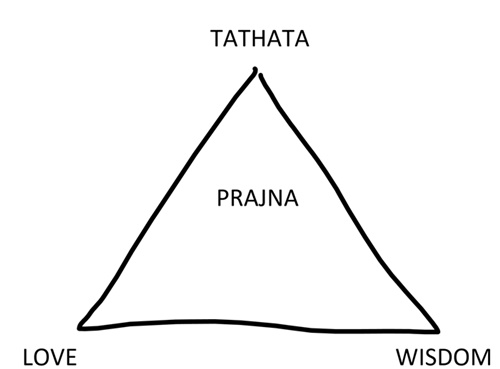

Yet we have to know that when the I is deconstructed we still function as human beings, in fact we function as better human beings without the attachments. So how can that be? Again he understood that through Buddhism so it is dogma. Through reconnecting with Dhamma – sunnata – during meditation, we develop the 5 Dhamma comrades of mindfulness, wisdom, concentration, love and the ability to embody these 4 comrades. Then there is the clarity (tathata) that arises from love and wisdom as part of what he now calls his prajna practice:– tathata, feeling , knowing and seeing the way things are. So the dogmatic answer to who am I is tathata, these comrades, the “pure” 5 khandhas and remaining unconscious attachments that have not been released. Because he has only just emerged from institutional Buddhism he can only describe the answer in terms of the teaching, although he recognises that the words and teachings are only rafts.

Perhaps eventually zandtao will become dogma-free but at the moment he does not see how that will be. Above there is dogma that is useful in helping zandtao answer “who am I?” If he moves away from this dogma and describes “who am I?” with different words, will they not be different dogma – just not institutional dogma? When Jac uses the term dogma-free, does she just mean free from established institutions but using a set of ideas that she describes? Isn’t that just a different dogma – Jac-dogma? Once we write we create a set of ideas based on the words we write, clinging to ideas is one of the upadanas zandtao works to release in his practice. At present zandtao can only use the words he knows and understands – to some extent – trying to be free of all clinging and attachment. But when writing words are used.

So we have rivers and rafts, rivers of torrents and calm, rafts of many types – even jetskis, and the other side? We leave from a bank that zandtao has described as patriarchal conditioning, do we understand (or agree with) what that bank is even with explicit words? Maybe we can talk of the other side as autonomous freedom but we don’t know what that is when we are going across. Who is the I that is crossing? And doesn’t the crosser need to know that I? Into all of this imponderable comes the boatperson who has to convey sufficient understanding of all that is imponderable before the seeker can cross. The duty of that boatperson is onerous there must be immense discussions of such boatcraft, let's consider them next. Let’s call this the crossing problem.

Be frank, zandtao, you are talking of teaching, why don’t you say so?

Why doesn’t zandtao call it teaching? To begin with consider the institution, in the suttas the Buddha called himself kalyana mitta – an advising friend, so is zandtao’s boatperson a teacher or an adviser? Yet most people see the Buddha as a teacher.

Let’s look at what Buddhist teaching looks like. It could be the same as 2500 years ago, a man in orange robes talking at a group of people listening – and it is usually a man talking about a wisdom practice. But now the orange robes sit in a building talking. Does a man talking lead to a seeker being able to cross to the other side? To even wanting to cross? Has this role of “man in orange robes talking at a group of people in a room” altered in any way for 2500 years?

What has happened over 2500 years is that there is mass education but unfortunately that mass education has little to do with what matters – “getting to and being on the other side”. However mass education has developed teaching craft. In mass education how we teach, how people are taught is questioned? Does similar questioning occur for spirituality? We have established the complexity of the spiritual crossing problem, but do we question how the boatperson can deliver?

In mass education we measure by achievement, education is successful if the student is successful. There are many delusions that arise in the description of success but the teacher delivers successfully if the student is successful. Let’s put aside the delusions that can dominate, and accept the solution to the crossing problem is if the seeker crosses successfully. With the path – the crossing problem, the seeker crosses or doesn’t. Clearly the activity of the boatperson has only one objective – helping the seeker cross.

In terms of the crossing problem the seeker needs to want to cross and the means to do so – the raft. If the raft is there but the seeker does not want to cross then the seeker does not cross. If the seeker wants to cross but cannot find a suitable raft then the seeker does not cross. The crossing problem is concerned only with how the seeker addresses the crossing problem. Whilst the boatperson can provide a raft, if the seeker does not choose that raft how can the seeker cross?

There are many rafts, many modes of transport even jetskis  , but if the seeker does not choose then the crossing does not happen. The teacher cannot make the seeker choose their raft. What is the teacher’s raft? The way the teacher crossed, what the teacher wanted and how they crossed. One methodology is that it worked for the teacher so it can work for the seeker, in other words the teacher forces the seeker onto the raft they have built for themselves and tells the seeker to cross. , but if the seeker does not choose then the crossing does not happen. The teacher cannot make the seeker choose their raft. What is the teacher’s raft? The way the teacher crossed, what the teacher wanted and how they crossed. One methodology is that it worked for the teacher so it can work for the seeker, in other words the teacher forces the seeker onto the raft they have built for themselves and tells the seeker to cross.

But what if the seeker doesn’t truly understand the raft? Can the teacher make the seeker understand? No. Only the seeker can understand for themselves, but because they are still seeking they cannot understand. It is not the fault of the seeker that they do not understand. The teacher understands their own raft because they have built it, but the seeker needs to build their own raft through their own understanding; then they can cross. So the teacher helps the seeker to build their raft, the teacher does not build the seeker’s raft the seeker does.

When a man in orange robes runs a meditation and then talks, how much help is being given for the seekers present to build their rafts? In the past seekers have built their rafts through dedication and repeatedly listening until they eventually understand enough to build their raft. But how much of this is the work of the teacher and how much is it the dedication of the seeker?

When a teacher explains how to build the raft, from the teacher’s point of view s/he is solving the crossing problem because the raft could be built and it worked for the teacher. In mass education at the beginning of the last century students wanted to learn, listened to the teachers, conformed to what the teacher wanted, learnt and passed the exam. This worked for the students who passed but many failed. Around the 60s and 70s teaching recognised the need for mixed ability teaching, teaching from where the student was at – bespoke teaching if you like. For those students who received this mixed ability teaching they became more successful, but it was never successful for all students because mixed ability teaching was expensive as the teacher had to dedicate time for developing a programme for each student. In a class of 30 with a teacher delivering at the front there is just one programme, in mixed ability there needs to be 30 programmes. If there were such 30 programmes and the students wanted to learn, then learning would occur and students would be successful. In mass education society does not want to fund 30 such programmes, and it is the case that students don’t want to learn for many reasons.

In spirituality it is different. Unless the seeker is deluding themselves they want to learn. But the teacher does not make programmes for the individual seeker, they persist in presenting their own raft and expecting the seeker to fit into their programme. What the seeker does is try and see until they find a teacher building a raft they can use.

The seeker does not know what their raft is or they would not still be seeking. A teacher knows their own raft but does not know what the seeker’s raft is unless they begin to know the seeker. If teachers became friends with the seekers so that they can learn what the seeker wants they can advise the seeker how to build their raft. Spiritual teaching needs to change from explaining the raft that has worked for the teacher to learn from the seeker what it is they want, and use their knowledge of the crossing to help the seeker build their raft.

The teachers have the knowledge, seekers do not – they come from a world of conditioning. Seekers must remove their own conditioning before they can build their raft, teachers can help them do that. Whilst this can happen in a classroom it is more likely to happen on a 1-1 basis, for some this is satsang. But if in the satsang the purpose is to squeeze the seeker into the teaching, then the raft is not likely to work. Given that the seeker knows the teacher has built a raft that has worked for the teacher, then the seeker-teacher relationship can be a dialogue to help the seeker build their raft.

Of course there are not enough teachers who have successfully built rafts so those teachers are forced to engage many seekers. But how fruitful is the time spent by the seeker in a lecture/classroom? And how fruitful is the 1-1 where the seeker gains through dialogue?

If existing institutions recognised this methodology more could be done. Within such institutions there are various levels of understanding. If a seeker is further along the path they can help novice seekers so long as this help is being monitored by the teacher who has built their own raft.

What happens to a seeker who comes to Jac? “In my work as a spiritual teacher I address each student individually. Together we explore and identify inhibitors to spiritual awakening. Each path is unique and, while certain issues are common to all, one also needs a tool kit for honest self-reflection and self-management.”

Next/Contents/Previous

|

|