Stephen is now looking at path, this will give zandtao an opportunity to examine his own understanding of path. Why is awareness connected with path? With awareness being spoken of so much, surprisingly this question is not asked; maybe there is not enough awareness in the world and therefore being aware is a step forward. But the path is concerned with action – on an exoteric level doing good things - sila. Do we always do good things when we are aware?

As a pathtivist zandtao looks at political awareness and sees very little correlation with good action, the distance between what we collectively know as right and what is done politically is huge. We cannot act without awareness but because we are aware does not mean that we act appropriately.

Ajaan Brahm addresses this issue as kindfulness, for him mindfulness is some form of awareness but awareness is not enough - we need kind actions to follow our awareness. When we see mindfulness being used by companies as a wellness means for improved work output, we have to question awareness per se - McMindfulness.

For Buddhadasa this is not an issue because in MwB he does not promote mindfulness alone but as part of his Dhamma comrades. Concentration improves mindfulness. With wisdom we use the mindful awareness to decide on action, and sampajanna ensures that we act. With mindfulness there is obligatory action because all Dhamma comrades arise from meditation. When zandtao considers magga he sees right action as a consequence of the Noble 8-Fold Path, yet elsewhere often mindfulness or awareness is considered in isolation without the action imperative. So when zandtao examines awareness there is an action imperative of sampajanna associated with that awareness, and with that action the seeker is following their path.

This type of approach to action has been described as integrated, integrating aspects of the person to ensure right action. Failure for such integration could be seen as bypassing. Spiritual bypassing is usually described as a meditator who chooses to withdraw from active daily life and meditates for the pleasure of jhanas, or chooses to live as a recluse because they are unwilling to participate in daily life. On a small scale when we become aware of a problem and don’t act on it, then we are bypassing. With integration, or with the Dhamma comrades, there is no such bypassing; integrated awareness means a response.

Stephen began his examination of path with awareness alone; this raised the action question for zandtao given Stephen’s possible intellectualism, it is an ego of sankhara-khandha that mental operations are mistakenly seen as sufficient. As soon as Stephen wrote of awareness zandtao was asking “how much are we aware of?” Zandtao notes a definition of mindfulness as 100% judgement-free awareness; given the action imperative already discussed, consideration of action, mindfulness awareness and judgement is key to what zandtao wants to address.

Let’s start with our bodies, how much are we aware of what is happening inside our bodies? Essentially very little. The complex natural functioning of the organs and the integral body functions within their own awareness are not parts of our awareness. How does our liver function? Zandtao has some summative notion that the liver functions as the body’s detoxifier but for most of his life he is not aware of what it does – he read that turmeric and black pepper helps the functioning of the liver but apart from doing this zandtao’s liver’s functioning has little to do with zandtao’s awareness. Except the time in his life when the liver didn’t function well. It was maybe 6 or 7 years after he had quit alcohol – bill was maybe 44 or 45, and his liver started playing up; in retrospect he amusingly calls it hepatitis-z. It was quite serious. He would wake up, work and by lunch-time he could not function, and went home, collapsed and slept on-and-off till the next morning; this went on for months. The doctor described it as liver dysfunction brought on by alcohol abuse although he had difficulty believing bill when he said he had stopped drinking. The problem did not appear to be clearing up. There was a new acupuncturist working at the local hospital; she treated the liver, and within 3 days had cleared up the problem – amazing!

Bill became aware to some extent of the liver functioning when it went wrong; in general as we get older, we get more and more aware of the way our bodies function as they start not to! But bodily awareness is limited as much of the body functioning we do not need to know. How much of our personality functioning is like this? How much are we aware of? In meditation we are encouraged to examine events that have caused issues. In this examination we look for egoic attachments that might have given rise to the problem, and then release the attachment. In our daily life how many of our actions are governed by egoic attachments?

What about events that happen in our daily life? How aware are we of what happens around us? How much detail are we aware of in those events? Hypnosis, does it help us remember detail that we are not consciously aware of? In terms of events that happen to us how much are we consciously aware? When our eyes see an event how much are we aware of what is seen? And if it matters how much more of the event are we able to recall?

And we can take this issue further with an understanding of shadow. As we grow up we might react to our upbringing. We might be asked by our parents to behave in a certain way, and because we have difficulty with this upbringing we fragment creating a shadow. What we have with shadows is behaviour that we are not aware of. We usually only become aware of shadows when their behaviour conflicts with behaviour that we would normally accept, we then become aware that it is shadow behaviour that is causing this disagreeable behaviour. So we are not always conscious of our behaviour in daily life, since that behaviour can also be governed by shadows that we are not aware of our actual behaviour might not be what mindfulness would choose.

Buddhism speaks of the 5 khandhas – kaya/body, vedana/feelings, sanna/memories and perceptions, sankhara/mental processes, and vinnana/consciousnesses. Khandha is translated as aggregate, and when they are aggregated together we consciously and unconsciously have the normal functions of our daily life. But there can also be conscious and unconscious attachments to the khandhas, and these can affect our behaviour.

So comes the Dhamma comrades, through mindfulness we observe and we develop love-wisdom, concentration and sampajanna to act appropriately. Does mindfulness observe all that happens and bring it to our attention? No, wisdom discerns what is appropriate for us to be aware of. We can use our concentration to become more aware in specific instances but for most of the actions in our daily life we are not aware of what happens.

This lack of awareness of minutiae is our normal functioning in daily life, we trust that nature functions appropriately. For most functioning of the khandhas, if there is a need for awareness consciousness will make us aware. Hence we can hear of remarkable survival stories as consciousness pools all khandha-resources to enable that survival. Normal human functioning trusts the natural functioning of the khandhas.

But this natural functioning does not distinguish attachments from normality; this natural functioning does not distinguish shadow and attachment from who we are – eg the Dhamma comrades. So naturally we can function with wisdom or we can function as attachment - or even worse the unconscious attachment of shadow. Zandtao trusts nature but not attachments. Zandtao has faith in the path and nature, but recognises that he must be wise concerning attachment and their release.

This is where Dhamma practice comes in. Through meditation we can develop the Dhamma comrades, and through their use become aware of attachment. If we let go of attachment then we can trust that we will be acting according to nature; but this is a big if. However this understanding also shows us that in life we do not have to be aware of minutiae as nature takes care of those, what we have to take care of is our practice so that attachments (shadows) are not causing actions we don’t agree with. Through integration, through the end of fragmentation, we can be natural and feel confident that we will have “right action”.

When Teal talks of fragmentation she talks of different selves acting in daily life. We naturally become more concerned when these selves acting are repressed shadow, but all kinds of behaviour can be associated with attachments that we might not have been aware of. In daily life people do not distinguish these actions from who we truly are, for other people to observe who we truly are then we need to become aware of attachment and release them.

If we accept this description then it means we can focus our attention on Dhamma practice, and know that our khandhas can function the way nature intended. We do not need to focus our attention on the khandhas, and wise practice then becomes discerning what is natural khandha and what is attachment; zandtao suggests this is why Buddhadasa described his practice as “removing the I and mine from the 5 khandhas”. Dhamma practice needs only be concerned with releasing attachments and developing the Dhamma Comrades so becoming conscious of the path, love-wisdom and tathata.

Stephen discussed awareness in the now. By focussing on a situation where anger was controlling a person’s awareness Stephen showed that awareness could be improved and that the improved awareness would be more conscious of what was happening. Greater conscious awareness of the NOW brings joy to life as we become conscious of nature, humane interactions as opposed to be locked into anger, future planning or past interplays.

To be negative such improved conscious awareness might be of advantage literarily, but mindfulness is aware of all around us and chooses what we become conscious of. How much did this anger reduce what mindfulness was aware of? How much has our mindfulness been reduced by these attachments such as anger? Either way, being stuck in anger is wasteful and can cause harm. If we are angry with a different situation, how often do we currently respond inappropriately with anger? The personality of anger reacts, this is not action based on love-wisdom, mindfulness and sampajanna.

With conscious awareness we can experience joys in the world often missed if we are clinging. But we must also be concerned in terms of our clinging as to whether our clinging affects how we act. Hence a need for no clinging in our awareness – improved awareness hopefully leading to right action.

And again this is where our dhamma practice comes in, how can we use our practice to improve how we act 24/7? “WHILE MEDITATION MAY be cultivated as a formal practice once or twice a day for half an hour or so, the aim is to bring a fresh awareness into everything we do” [Stephen's BwB 32.11 ]. Total agreement with this. Eckhart is not a fan of the morning/evening rituals of meditation because his objective is living in the present moment 24/7. Whilst the objectives are the same zandtaomed encourages twice daily meditation in which MwB is practiced so that during the day the seeker can live in the present moment 24/7 with mindfulness, love-wisdom and sampajanna. This daily practice helps release attachments picked up during the day as well as developing the bhavana process of improvement integral to MwB. Eckhart encourages mindful moments in which if attachments are arising mindfulness can swoop in and help us let the attachment go – definitely a good practice and one that zandtaomed would advise.

“MUCH OF OUR time is spent like this. As we become aware of it we begin to suspect that we are not entirely in control of our lives. Much of the time we are driven by a relentless and insistent surge of impulses” [Stephen's BwB 32.7]. If this is the only reference to the impulses of conditioning then for zandtao it is not sufficient for understanding tathata, and for understanding what the path is. From birth and throughout our upbringing we make agreements with parents, teachers and adults in general as to how we will behave in society; in some cases we disagree but are forced to fit in, and these disagreements formulate as shadows. By the time we are adults there is a whole basis of conditioned egos that enable us to survive in society, but as we mature we let these egos go as we develop awareness with mindfulness, love-wisdom, concentration and sampajanna.

Do we always mature? This is the problem of conditioning because in society we are not encouraged to mature. Our upbringing produces kilesa, and these kilesa have become so entrenched in our societies that the conditioning continues as adults; the falling away of egos that would naturally arise with maturity doesn’t happen because of this ongoing conditioning. In fact this mature process has now become an anathema to the society’s conditioning, and such mature people end up in conflict with the systemic conditioning – the embodiment of kilesa in our society is best understood as patriarchy (it is worth taking time to consider how true it is that kilesa conditioning is embodied as patriarchy - Seeker Story).

For mature seekers following the path is to go beyond this conditioning, seekers can begin to see conditioning for what it is – tathata – see things the way they are. When Stephen is speaking of impulses, he is talking of new sense events – in this case the barb his acquaintance S threw at him. From conditioning there are egos reacting to this barb (impulse or new event) reinforcing the attachments conditioning. If we cannot step beyond this conditioning then our lives are controlled by these impulses that keep coming at us. Fortunately we are given the tools of our Dhamma practice to help us go beyond the conditioning. Through Dhamma practice we release the conditioned egos we grew up with and we go beyond the ongoing conditioning society throws at us. This is part of tathata – the awareness of conditioning – seeing things the way they are. And seeing the path as going beyond conditioning.

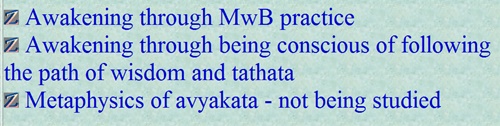

Could Stephen's diminishing of the understanding of conditioning to impulse – idappaccayata-paticcasamuppada to impulse – be by intention, as a consequence leading to reductionism because of his desire for secular Buddhism? Hypothesis – Stephen has chosen to focus on Theravada for his secularisation. From zandtao’s outside position Mahayana can be seen as focussing too much on the esoteric, and as Thay said did not focus enough on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness ("Awakening of the Heart" by Thich Nhat Hanh). Or as Stephen might say – not enough focus on the 4NT. It would then be an error to see Theravada as lacking in this “esoteric”. The essence of Buddhadasa’s “removing the I and mine from the 5 khandhas” is an understanding that what remains – sunnata – is that which is true. Sunnata is not nihilation but voidness of self which is “full”. Has Stephen chosen Theravada because it is easier for intellectualism to reduce Buddhism to a rational practice? There were earlier indications that Stephen was not doing this, but his failure to emphasise certain connections is making zandtao question. As stated above - “awakening through being conscious of following the path of wisdom and tathata” is for zandtao an essential part of Theravada.

“Worrying about what a friend said can preoccupy us so completely that it isolates us from the rest of our experience. The world of colors and shapes, sounds, smells, tastes, and sensations becomes dull and remote” [Stephen's BwB 32.8]. Whilst this is an important aspect of awareness, more important is path awareness - “awakening through being conscious of following the path of wisdom and tathata”.

“Awareness is a process of deepening self-acceptance. It is neither a cold, surgical examination of life nor a means of becoming perfect. Whatever it observes, it embraces. There is nothing unworthy of acceptance” [Stephen's BwB 32.12 ]. It appears that within each positive understanding Stephen introduces a reduction to suit his secularisation. Consider zandtaomed’s 3-memes:-

Our path is to prepare the best vihara, and by the vihara zandtaomed means the khandhas of kaya, vedana, sanna, and sankhara – body emotion and mind. This is why we meditate – to release attachment so that the vihara is as good as we can make it. Can it be perfect? Zandtao does not know but his own vihara is far from perfect. Zandtao also avoids any form of perfectionism because that introduces failure. But one purpose of meditation is to release attachment to prepare the best vihara – the best we can do.

Do we do this through awareness alone? Deepening self-awareness helps us to understand where we have attachment, where attachment has arisen. But awareness of attachment is not enough, we use mindfulness, love-wisdom and sampajanna to remove the attachment and live a better life. Being aware of attachment is not enough. Whilst we embrace and accept attachment, we also recognise the need to release attachment if possible – no aggressive compunction gently letting go. It is often the case that shining the light of awareness on egoic problems will release the ego but not always, then we need the active approach of mindfulness, love-wisdom and sampajanna.

“The task of awareness is to catch the impulse at its inception, to notice the very first hint of resentment coloring our feelings and perceptions. But such precision requires a focused mind” [Stephen's BwB 32.16]. We accept attachments for what they are – anger etc, observe them without judgement rather than identify them, and try to catch the “impulse” at inception. This is Idappaccayata-Paticcasamuppada. Buddhadasa highlights two steps within paticcasamuppada, the first step overcoming ignorance – without ignorance egos cannot become - and the point of contact phassa when the very first hint of anger arises and at that contact we don’t let attention cling so we don't give birth to anger.

“This is not to say we never suffer from bouts of excitement or lethargy, but it is possible for consciousness to become increasingly wakeful” [Stephen's BwB 32.25]. Stephen discussed characteristics such as restlessness that might arise, and accepting them; zandtaomed thinks this is a sound approach. Which characteristic are you particularly susceptible to? One for zandtao is restlessness – a restless mind; these are the restless operations of his sankhara-khandha. Noting this zandtao pays attention to this sankhara-khandha and uses the ability. This has happened naturally as he tries to work through his understanding of the path especially through writing. There is no repression of sankhara-khandha but there is using it at an appropriate time; when it is used appropriately there is less need for restlessness. What about kaya, is kaya restless because there is not appropriate exercise? Do our emotions interfere because we repress emotions generally? Is our meditation full of memories and perceptions because we do not pay attention to sanna-khandha? Our khandhas need to be used, if they are not being used they will tell us through restlessness or lethargy; note if restlessness arises we use mindfulness, love-wisdom and sampajanna to change this awareness to action.

Above, mindfulness is considered as 100% judgement-free awareness. Consider the divisions of right and left within western society, increasingly neither can discuss with each other; it is almost as if there is an entrance requirement of views before a conversation can be started. For the left this might be a form of socialism, and for the right it might be a recognition that “women and non-whites are taking their jobs”. Yet we are all people together, so in conversation we enter without any requirement – not to proselytise our views, but together as people to reach a common understanding. Clinging to views is known in Buddhism as ditthupadana.

We could conceive of holding to views as wearing blinkers whether socio-political views or otherwise; when there is mindfulness of judgement-free awareness no such blinkers hinder our understanding and practice. This raises a legitimate question concerning Stephen and his secular Buddhism, has he approached the teachings with a view to finding a secular approach? Has he used blinkers to sift out teachings that do not suit his secular agenda? This is for Stephen to consider.

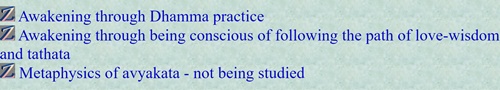

As far as zandtao is concerned there do appear to be blinkers that he explains in this way. Stephen focusses on awakening through 4NT dharma practice - there is some close comparison with Buddhadasa’s awakening through MwB practice. Stephen then describes what is not dharma practice as metaphysics. It appears to zandtao that Stephen includes the avyakata as metaphysics, but in Stephen’s metaphysics he also includes some of zandtao’s second awakening prong - “awakening through being conscious of following the path of wisdom and tathata”. It is not clear to zandtao where the boundaries of Stephen’s dharma practice and his metaphysics lie. Zandtao feels strongly that in the process of awakening being conscious of following the path of love-wisdom and tathata is important – consciousness of the path is central. What we have to be clear about when considering a possible secular approach is whether we are clinging to ditthupadana, clinging to an intellectual ideal that there can be a secular Buddhism, and through that clinging seeing the teachings through blinkers. Zandtao sees that zandtaomed’s advice can be beneficial for a non-secular approach but there are two provisos that he makes. Firstly there is an upadana point in religion, beliefs that will be unintentionally questioned when reconnecting with Dhamma. And secondly the purpose of MwB Dhamma practice is awakening, so what happens to those of other religions practicing this Dhamma when they begin to feel awakening? Do they repress it? Do they accept it bringing with that acceptance questions concerning their own creed (upadana)? Undoubtedly Dhamma practice is beneficial for all people but given these two provisos can it possibly be called secular?

Such a blinkered approach would bring with it restlessness as with any approach that is not true - clear vision. Is there restlessness with MwB? Zandtao’s meditation is based on MwB – "Mindfulness with Breathing" by Buddhadasa Bhikkhu. Buddhadasa called his method anapanasati bhavana that is usually translated as MwB – Mindfulness with Breathing. Anapanasati can be directly translated on its own as Mindfulness with Breathing, so what is the bhavana? Zandtao thinks of this as development so that within MwB there is a development imperative. But what is the development? Following a path towards awakening – Buddhadasa might well have described this as reconnecting with Dhamma. Buddhadasa’s meditation is a dynamic process of development – bhavana. What if there were no development? Then the path might disturb, and these disturbances might be shown as restlessness, agitation or even path anxiety. For zandtao the purpose of the khandhas is that they are tools to function in daily life, and they are also tools to help seekers follow the path. If the path is not being followed then these tools will react with restlessness and agitation creating egos.

How would such tools react if the path was not recognised? If there were a blinkered clinging?

Stephen says consciousness can become increasingly wakeful, this is important. Fits in with the bhavana of MwB.

“To meditate is not to empty the mind and gape at things in a trancelike stupor. Nothing significant will ever be revealed by just staring blankly at an object long and hard enough. To meditate is to probe with intense sensitivity each glimmer of color, each cadence of sound, each touch of another’s hand, each fumbling word that tries to utter what cannot be said” [Stephen's BwB 32.34 ]. Stephen’s meditation method is very much concerned with awareness in the NOW. Given his meditation method where is the development of consciousness?

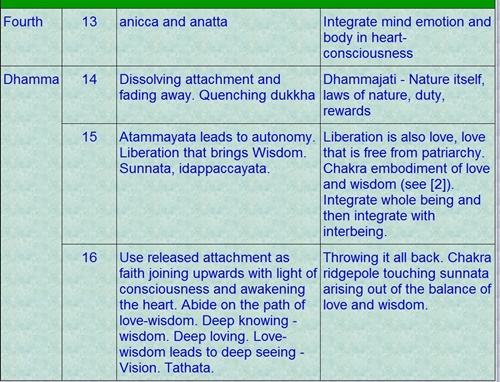

With MwB there is bhavana, consciousness developing. MwB has 4 tetrads corresponding to the 4 Foundations of Mindfulness which zandtaomed thinks of as kaya, vedana, citta – sanna and sankhara, and reconnecting with Dhamma. Given this meditation framework the Dhamma practice is very different to Stephen’s. With reconnecting with Dhamma we already have why zandtao views awakening with 3 prongs:-

Stephen has two prongs:- Awakening through the Dharma Practice of 4 NT, and metaphysics that is not studied.

If we examine zandtao’s own zandtaomed practice we can see a fundamental difference with Stephen. Let zandtao focus on the 4th tetrad only:-

[Retroactive edit problem - this 4th tetrad now includes practice for love-wisdom balance that arises from part 3 of this z-quest. Including love improves practice but does not affect what zandtao is writing here.]

Zandtaomed’s 4th tetrad is the basis of a path for zandtao. This is zandtao’s practice and in his advice he asks seekers to arrive at their own interpretation of Buddhadasa’s 4 tetrads including their own interpretation of the path. So zandtaomed would hope to see a practice that was individual and different.

The meditation method is not neutral, it links with the love-wisdom, study and understanding of the seeker. If the advice is to require all meditation methods to be the same then that advice needs questioning. But at the same time if the meditation method is didactic, directional and purposive that also needs questioning as it could have attached egos. Within the framework of the Buddha’s 4 Foundations zandtao would advise each seeker to observe their own path, and adjust their MwB accordingly. Within the Dhamma practice of the 4NT zandtao would expect to see each seeker develop their own understanding of magga, their own understanding of right view, right intention, etc.

The keyphrase is for the seeker to “observe their own path”, not fashion their own path but observe it, and the best place for such observation is meditation. So whilst Stephen is observing NOW zandtaomed is observing the path, as path might well include metaphysics for Stephen then what is zandtaomed observing? Zandtao’s answer is path, is Stephen’s answer metaphysics? And if the answer is metaphysics, does that mean Stephen's approach ignores what zandtao sees as path?

Because meditation is concerned with the inner journey then zandtao favours all meditations, but his path clearly chooses a meditation with bhavana. How Stephen has described his meditation practice is different, simply by observing the 2 practices zandtao can see Stephen’s 2 prongs arising as compared with his own 3 prongs arising from MwB. The meditation method is fit for purpose leading to questioning, are the methods unconsciously chosen for purpose?

Zandtao will not judge Stephen’s meditation method and purpose, that is for him to examine. Nor is it sensible to be critical of his own meditation method because it is different to Stephen’s – it is part of the totality of his path. In fact given the differences highlighted so far, it would be unreasonable to think the meditation methods would be the same; meditation method is part of autonomy – perhaps the central part?

Next in his book Stephen looks at conditioning which he calls becoming. He begins with this that he quotes as The Buddha:-

“Confusion conditions activity, which conditions consciousness, which conditions embodied personality, which conditions sensory experience, which conditions impact, which conditions mood, which conditions craving, which conditions clinging, which conditions becoming, which conditions birth, which conditions aging and death”.

—The Buddha” [Stephen's BwB 34.1 ]

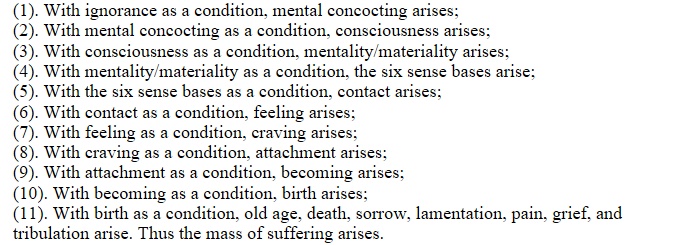

The version zandtao uses is from Buddhadasa:-

““And what is dependent origination? Ignorance is a condition for choices. Choices are a condition for consciousness. Consciousness is a condition for name and form. Name and form are conditions for the six sense fields. The six sense fields are conditions for contact. Contact is a condition for feeling. Feeling is a condition for craving. Craving is a condition for grasping. Grasping is a condition for continued existence. Continued existence is a condition for rebirth. Rebirth is a condition for old age and death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, sadness, and distress to come to be. That is how this entire mass of suffering originates. This is called dependent origination” SN12.1

In the sources and notes Stephen writes “Confusion conditions activity . . . is my rendition of the Pali formulation of what are commonly known as the “Twelve Links of Dependent Origination”” [Stephen's BwB 48.41]. Given the other 2 sources zandtao has quoted, does Stephen have the right to follow his rendition with “The Buddha”? Specifically zandtao is unhappy with the translation of ignorance as confusion, but does it matter when zandtao has rejected Stephen’s secularisation? In Stephen’s section on awareness, zandtao discusses idappaccayata-paticcasamuppada noting going beyond conditioning.

Zandtao sees ignorance as a lack of wisdom in line with Buddhadasa’s 4 Dhamma comrades. It cannot be said that knowing ABC means “you are not ignorant”; wisdom is different to factual or text awareness. Given “awakening through being conscious of following the path of wisdom and tathata” this wisdom is far more than not knowing “facts or texts” – it is at least understanding.

Zandtao has also seen this “confusion” translated as delusion. Delusion is closer to confusion and for zandtao gets towards seeing clearly – tathata. When we go beyond conditioning and see clearly, then we do not get sucked into seeing the stream of conditioning as total reality. When people accept the stream of conditioning as total reality then it is like their lives are controlled by impulse – causes and conditions. But if we “step beyond” then we can see the way we are expected to respond and can make choices. Can we change the way causes and conditions come to us? No. Can we see the way these causes and conditions expect us to respond? Yes. Do we have to respond in this way? Using mindfulness, love-wisdom and sampajanna perhaps we don’t? Or with mindfulness, love-wisdom and sampajanna we do what causes and conditions would expect of us but with detachment.

“This confusion is not a state of darkness in which I fail to see anything. It is partial blindness rather than sightlessness” [Stephen's BwB 34.4]. Zandtao likes this, this description of confusion could simply be lack of vision of the path. When we don’t see the path there is confusion giving rise to the restlessness, for example - previously discussed. “I have a strange sense of inhabiting a reality in which I do not quite seem to fit. I suspect that I keep getting tangled up in things not because I fail to see them but because I imagine myself to be configured other than I am. I think of myself as a round peg trying to fit into a round hole, while unaware that I have become a square peg” [Stephen's BwB 34.6]. Bill recalls his confusion at upheaval as well as his confusion prior to upheaval. Prior to upheaval bill had no idea, he was just bouncing from pillar to the post of conformity without any motivation, in his mind there was confusion but it was just there – the confusion was unconscious. What was being done was the conformity, but the confusion was that bill had nothing to do with this conditioning. As soon as the conformity was confronted – by his failure in work because of disinterest, the path came in. With it came the consciousness that the path was right but bill was mostly ignorant of the path – he lacked love-wisdom. Through his 2nd childhood experience brought with it some love-wisdom, and the more wisdom the less confusion.

Here's the rub, bill was fortunate to start the path at 23. Although it brought with it conscious confusion, he found that the learning of wisdom that started with that upheaval reduced the overall confusion. In the world of conditioning how many people just live in their conformity of conditioning with the unconscious confusion never knowing that there is a path – never even partially awakening to the path. How do we end this confusion? Such a big question. To begin ending it we need Dhamma practice, if we “need to conform” to anything it is the siladhamma of dhamma practice – not conditioning. Acting through sila is not necessarily awakening but it is a world without confusion – we know what to do. Whilst the world around us is conditioned, our actions are not because they are guided by sila.

As we live our daily lives through sila, our dhamma practice develops the Dhamma comrades that continue ending confusion until there is clear vision of the path; this is the process of awakening. If we develop zandtao’s 2nd prong - “awakening through being conscious of following the path of wisdom and tathata” – seeking awakenings by recognising insights etc – being conscious of the path, then zandtao feels the progress is quicker – he feels knowing and seeing the way things are (wisdom and tathata) happens quicker. Living through sila is the dhamma practice that is secular as it does not recognise awakening nor does it pass the upadana point. But what about confusion? There is no confusion as to our conduct because sampajanna leads to sila, but is there confusion concerning awakening if we are not looking to be conscious of it? If we are not looking to be conscious of it, can it arise? If we limit ourselves to the good practice of siladhamma – without seeking conscious awareness of the path, will there be a new confusion developing? There is confusion of the path seeking itself but not being able to consciously recognise that path if it arises; this is a repression of reality that causes confusion.

Is this path magga? It can be. With magga we are given right conduct that is sila but there needs to develop wisdom that is recognition of the path. Does wisdom arise from magga? It can do if we allow it - in magga panna is taken as right speech, right action and right livelihood, but if we are not seeking recognition of that wisdom and vision (panna and tathata) then is it going to arise? The conduct of magga is sila – good conduct; is magga also the quest for wisdom and tathata? It is the conduct required that can lead to the path of wisdom and tathata if we choose to be aware of it.

After questioning Stephen’s use of the word confusion zandtao has used the term to explain the path. Wisdom is usually described as the ending of ignorance, the development of tathata; lacking tathata there is confusion. Now zandtao has a clarity of Stephen’s usage but explained in terms of zandtao’s second prong, what is confusion if it is not seeking path – developing tathata through clear seeing.

However if Stephen is avoiding the use of the term “ignorance” because there is the delusion that ignorance can be overcome through study alone – ending ignorance through factual knowledge, then zandtao understands that. Ending of ignorance is the development of wisdom, and study is only a part of that.

Zandtao maintains that these 3 prongs are in line with “What the Buddha taught”:-

If we accept Buddhadasa’s wisdom then awakening through MwB practice is “What the Buddha taught”; in terms of the teachings of the suttas, MwB could be described as an interpretation of following the 4 NT and the 4 Foundations of Mindfulness. When you combine this with the awakening of the 2nd prong - “awakening through being conscious of following the path of love-wisdom and tathata”, then we could be arriving at awakening through feeling, knowing and seeing the way things are by following the 4 NT and the 4 Foundations of Mindfulness - leaving aside the avyakata that cause mental confusion as in zandtao’s view we are not given the mental capacity to answer these avyakata questions.

Zandtao has already recognised that in terms of secularisation asking people to accept awakening might cause conflict with views from other religions. But what about the 3 prongs as a view of “secularisation” within Buddhism? Could it be accepted that the 3 prongs are a common core for all Buddhisms? Zandtao would not presume to go any further with this question, that is for Buddhist scholars and adherents to the different Buddhisms.

But considering Stephen’s mission then we must ask if awakening can be accepted by other religions. Zandtao feels that Stephen’s secularisation of reducing Buddhism to dharma practice (his dharma practice and metaphysics) “plays down” what awakening is, this could be a tactic of secular acceptance. But what if awakening could be considered by all as human nature - a person with love, wisdom and vision. That could possibly be accepted, but to arrive at that awakening MwB practice goes through an understanding of sunnata and the 3 characteristics of anatta, dukkha and anicca. Zandtao’s limited understanding of sunnata would as a view go beyond the upadana point. Zandtao suspects that the 3 characteristics would be considered difficult culturally especially in the West. Anatta as no-self would contradict personality culture, the materialism of capitalism would find dukkha difficult, and anicca feels a contradiction for a culture that is striving for a “dream”. However culture and religion are not the same so there might be potential there. This question of the different acceptances by culture and religion arises because Buddhism is a “way of life” rather than a religion, and culture is clearly a part of the world’s way of life.

There is more likely to be mileage in investigating why Buddhism cannot be secular rather than asking for it to be accepted as secular by other religions. Dhamma practice itself is secular as it is fundamentally siladhamma without awakening, and siladhamma is common morality for all – not a specific “Buddhist morality”. Asking people of other religions whether they should be looking towards love-wisdom and vision as part of their religious practice is a question worth asking, and a question worthy people from other religions would want to answer – and would presumably advocate as arising from their own religious practice. Questioning whether life is suffering and how much their religion and cultural practice contributes to that suffering is again a question for all worthy people.

Anatta and sunnata however are realities that require experience. “Removing I and mine from the 5 khandhas” is intellectually difficult for anyone to understand, it is only through glimpses that these realities take on meaning. Asking whether there is a self, whether we could be considered as sunnata with the aggregates of the khandhas – kaya, vedana, sanna and sankhara with associated consciousness (vinnana) might be questions some worthies would choose to grapple with. But these two are path questions that might be suitably addressed as “advanced” ie for those taking a secular path further; by then paths of all religions would have met and such intellectual division would not matter.

“Again, I need to stop. I may be able to start thawing this isolation by focusing on the complexity that I am. I may be able to ease the spasm of self-centeredness by realizing that I am not a fixed essence but an interactive cluster of processes” [Stephen's BwB 34.15]. Stephen describes the confusion and turmoil that places him in isolation and conflict. Here he describes viewing himself as a complexity or an interactive cluster of processes as a way of escaping this turmoil.

It is worth considering that this confusion and turmoil arises naturally through the conditioning that helps us survive being young. Once mature this confusion and turmoil just falls away. Why? Because the conditioning is intended to create self-esteem and through this self we survive. But when it comes down to it this self is a collection of attachments that provide the young with protection in daily life. But once mature we don’t need such protection because we become aware of who we truly are – Dhamma comrades/sunnata. We then realise that the very attachments that gave us the self-esteem are preventing us from living who we truly are – just by being without attachment. So the way of avoiding the confusion and turmoil is to detach ourselves from the conditioning process itself. This is awakening.

We let go of this self that has been conditioned – created through the conditioning that dominates our social interactions; this is anatta. But how do we live without a self to guide us? This is the interactive cluster of processes known as the khandhas. Each human has a body that functions, vedana that emote, sanna that perceives, and sankhara that operates; they have their own functioning, there is no need for direction. If there is no direction, what are we doing? Sunnata – consciousness living and being, consciousness evolving through love-wisdom and tathata. What prevents us from knowing and seeing this? The very conditioning that helps us survive childhood. Sadly as adults we have not recognised the maturity that lets go of the confusion and turmoil of this conditioning so we remain attached confused and in turmoil. This recognition of conditioning is awakening through dhamma practice and “awakening through being conscious of following the path of love-wisdom and tathata”.

Stephen’s recognition of the confusion and turmoil leads him to isolate as I that separates as “the bit that is mine and the bit that is not” bringing order in his own life. But if there is acceptance that there is conditioning and there is the work to go beyond that conditioning then there are not separate “bits”, there is the unity of interbeing in which the mature move beyond the confusion and turmoil of conditioning.

Then Stephen gives us a meditation to help us make sense of the confusion and turmoil concluding with “If the self feels like a physical sensation, then probe that sensation to find what it is. If it feels like a mood, a perception, a volition, then probe them too. The closer you look, the more you might discover how every candidate for self dissolves into something else. Instead of a fixed nugget of “me,” you find yourself experiencing a medley of sensations, moods, perceptions, and intentions, working together like the crew of a boat, steered by the skipper of attention” [Stephen's BwB 34.23]. Here Stephen is going through a process of anatta – disidentification with the khandhas of body (kaya), mood (vedana), perceptions (sanna) and volitions (sankhara) leading to “yourself experiencing”.

But take that meditation a bit further, and you can observe and experience at the same time – observing and experiencing at the same time, observing and experiencing that are not separate but two aspects of the same event. Mindfulness observes whilst there is experience and is the “skipper of attention”. As we promote mindfulness (and the other Dhamma comrades) through meditation we learn to focus our attention. And through the Dhamma comrades there is a choice of attention, a choice of the experiencing of the khandhas – a choice beyond conditioning.

In the next section after describing how the conditions of confusion and turmoil impact on him Stephen said that “these seemingly irresistible feelings, perceptions, and impulses are not the only options. For in the immediacy of that experience lies the freedom to see more clearly. I can stop, pay attention to the breath, feel my beating heart, and remember to be aware. Then I may respond with care and intelligence to the snake’s presence. Or realize it is just a coil of hose” [Stephen's BwB 34.30]. Living a life of conditioning is not the only option. Through developing mindfulness, we can observe and experience at the same time. This mindfulness enables us to stop and be aware, then our response need not be conditioned, but can be based in love-wisdom.

Stephen then spoke of the temporary fulfilment of desires. Again this is observation. There is a desire, we fulfil it but it is only temporary, and then a new desire comes back. We can be driven from pillar to post by desire and fulfilment, because once fulfilled there is nothing and new desire comes. With acceptance of the way things are – tathata, we observe desires coming and going, we don’t crave, we watch them rise and fall. We learn there is no fulfilment in desire, but there is fulfilment in path. We have khandhas that need to function; and once that functioning is out of the way – balanced, there is just the path we follow that brings peace. As we observe the 4 foundations, as we contemplate their fulfilment, then we reconnect with Dhamma, evolve consciousness through our quest into the unknown, and there is peace.

Autonomy has taken on increased importance in zandtao’s understanding of the path to awakening, as said in Ch6 autonomy is needed to enable wisdom that can lead to awakening. When we look at conditioning we see where autonomy arises, it is beyond conditioning – the autonomy is the state of being beyond conditioning. It is not self, it is not individual in the sense of belonging to me or mine, it is that which goes beyond conditioning.

Autonomy becomes very important when we consider the path. In Viveka-zandtao the path was honed down to essence, we have the external path as the way we live our lives but from the outside that is indistinguishable from our daily lives. As a teacher, was bill’s path teaching? It was his way of life but he was not in control of what he taught and mostly not in control of how he taught; there was however an essence of his teaching that was path. That essence can be more clearly seen in the initial decision to become a teacher following upheaval. Upheaval brought with it a compassion imperative, and that compassion took him into working with kids, and then the formative compassion of working with kids which as an ideal was teaching. Teaching then provided the finance that took him through 2nd childhood, and provided the finance for retirement and the serious work of the path.

Bill’s way of life was teaching and it was his vocation. A component of that teaching was path, but to identify path with his practice of teaching would be far from true. He gave up teaching after the Inner London school, returned to teaching because he needed money for his relationship, and then teaching enabled him to travel. And when his path was too distant from the teaching there was finance that enabled early retirement and the ability to begin serious study on the path. But that study was not path even though zandtaomed would have said he was following his path, there was a path essence that study was seeking. As an elder zandtaomed pinpointed that essence as inner guide, but then he crossed the threshold of autonomy.

And then in Ch6 it was recognised that autonomy was required to experience wisdom, experiences of awakening, that can hopefully lead to full awakening. Seekers need to recognise this autonomy, develop this autonomy as part of their path towards the gaining of wisdom and increased awakening. The path is obviously important but it is the autonomy we develop as part of that path that seekers need to recognise, the seeker gaining autonomy. Autonomy is the path essence that comes from the path, the path is finding autonomy; that is now the zandtao purpose of this z-quest – finding autonomy.

Next/Contents/Previous

|