|

From the time that zandtao crossed the threshold of autonomy zandtao's writing in the Prajna portal has become part of a personal journey into the unknown. For all seekers zandtaomed feels there is a point of autonomy where their own seeking leads them into their own journey into the unknown, and as such it is not part of zandtaomed – zandtao’s meditation advice for building a practice. So what zandtao has learnt through the unknown after crossing the threshold is his own path, and does not necessarily have application for the practice of seekers working with zandtaomed.

But there is one exception because of omission – the embodiment of love in meditation.

Zandtao’s prajna (understanding after crossing the threshold of autonomy 2 or 3 years ago) has been concerned with love and patriarchy. The understanding of patriarchy is part of the Seeker Story at the end, but at that stage the seeker is so close to their own autonomy that the negative attachment distractions of the understanding of patriarchy hopefully would not adversely affect the development of their practice. Understanding of patriarchy helps us to recognise that love and patriarchy are in many ways inimical, and this understanding is important given that a practice without love is not complete. The relationship between love-wisdom and patriarchy has been examined briefly in the reflection on Equanimity, Patriarchy, Genuine Leadership and Going Beyond, it is also discussed below, and is a central theme of Real Love.

When we look at Buddhism we can observe a representational patriarchal bias amongst the monastics with the preponderance of male monks. Western monastics within Buddhism are leading a change to overcome this bias, but entrenched within Eastern tradition is a masculine bias that resists these efforts for legitimate change. Equally within this Eastern tradition is a rejection of western ego (as with all egos), and unfortunately parts of the establishment of these traditions associate this western ego with emancipation of women - some see such emancipation as an ideal (ditthupadana) rather than seeing it as a bias that has arisen through institutional compromise with patriarchy.

Until recently zandtao's path studied Theravadan Buddhism, mainly Ajaan Buddhadasa. Within that school of Buddhism was the appalling spectacle that arose around the Bhikkhuni ordination carried out in 2009 by Ajaan Brahmavamso (Ajaan Brahm), as a result of which he was excluded by his order - the Forest Sangha. Zandtao was living in Thailand then, and it was played down by the orthodoxy yet it was highly significant in demonstrating how entrenched even overt patriarchy is within Theravada Buddhism. When you look at the robes within Eastern Buddhism as a whole, there is an observable bias and wise enquiry has to wonder as to how serious the problem is.

That observable bias is for those traditions to address. At the time of the ordination (and at other times), Theravadan Buddhist seekers (and other Buddhist seekers) have to ask themselves about this bias, wise enquiry being part of a good practice – 7 components. For those of us concerned about this bias there was a general understanding that the Buddhist sut(t/r)as and teachings themselves did not contain such bias yet across all Buddhism there is an observable bias amongst monastics. This bias is so observable, genuine wise enquiry is required to ask of the sut(t/r)as and teachings not whether there was bias but how much bias there was in the teachings? And more seriously how much that bias affects the path?

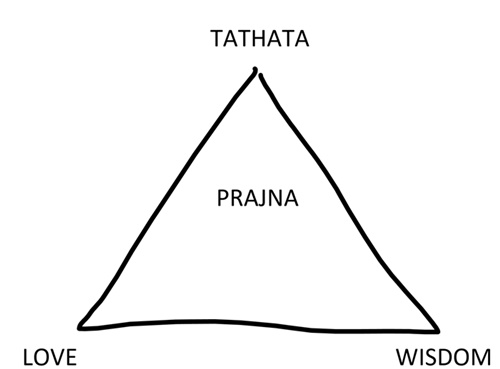

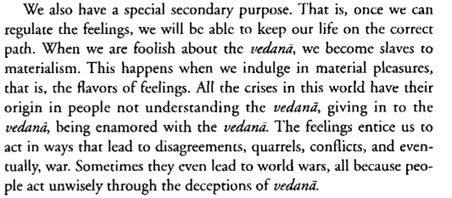

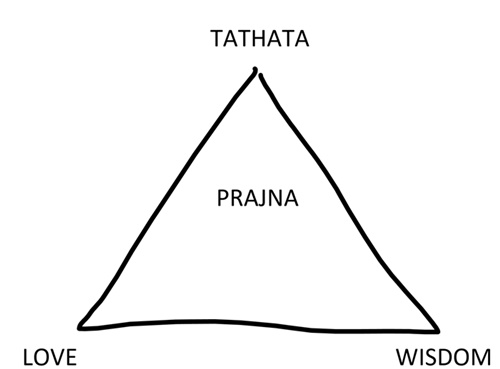

For some, tathata (the way things are) is a culminative key understanding of Buddhist practice. Within the first sutta, Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, in which the Buddha talks of the 4 Noble Truths, there is a key phrase of tathata before the Buddha describes those truths – knowing and seeing the way things are; this zandtao corresponds to wisdom and tathata. Why isn’t the phrase – feeling, knowing and seeing the way things are; this zandtao corresponds to love-wisdom and tathata.

What this depiction clearly points out is the need for love to see clearly. Throughout Buddhism there is a need for love but how much love is emphasised as with the key phrase already mentioned is a big question.

When zandtao talks of love and patriarchy being inimical, he is not saying love is feminine and wisdom is masculine and that is why compromise with patriarchy allows for wisdom; love-wisdom balance is for all. Nicola Amadora was a key influence on zandtao, and she promotes the feminine way and her path is concerned with love – listen to her Batgap interview. Nor is zandtao saying that men promote wisdom and women promote love, but what he is saying is that patriarchy allows for wisdom and patriarchy marginalises love, yet for zandtao the path needs a love-wisdom balance to truly see tathata. Does that love-wisdom balance necessarily arise out of the sut(t/r)as and teachings of Buddhism?

As zandtaomed, zandtao advocates a practice that revolves around Buddhadasa’s Mindfulness with Breathing - MwB, and he balances this with his own book Companion mainly to include understandings that arise from the Seeker Story. In neither MwB nor zandtaomed’s Companion is there an emphasis on love. ( - that needs to change or at least noted in the Companion). - that needs to change or at least noted in the Companion).

Our practice is central to who we are, and for Buddhadasa MwB was his practice. Where does love fit in to his practice? Love is elsewhere in his teachings - he talks of the true love of Dhamma love, but is not explicit in his practice even though the brahma-viharas come in in step 9; Thay called the 4 brahma-viharas the 4 elements of true love.

Key to his practice is the arising of the 4 Dhamma Comrades – sati – mindfulness, panna – wisdom, samadhi – concentration, and sampajanna – embodiment; zandtao often translated sampajanna as wisdom-in-action. Why isn’t love a Dhamma Comrade? Why isn’t sampajanna love-wisdom-in-action? It is for zandtao and zandtaomed now, he talks of 5 Dhamma Comrades and sampajanna as embodiment – love-wisdom-in-action.

But this omission is not as notable as the possible problem with vedana in MwB. MwB follows the structure of the 4 Foundations of mindfulness of which the second is vedana. In his book MwB Buddhadasa entitles the section on vedana as “Mastering the vedana”. This phrase describes what happens with Buddhadasa’s teachings. In Buddhadasa’s MwB each of the foundations is a tetrad and has 4 stages, and the final stage of Buddhadasa’s “mastering of the vedana” is calm leading hopefully to the perceiving of cool as Nibbana. For Buddhadasa mastering vedana – mastering feelings – is to calm them.

This reads like calming the vedana to help us control the mind before following the path. Zandtaomed's practice is now different. During the second tetrad zandtaomed is using Buddhadasa’s stages to develop feelings of spiritual love, and it is this love in combination with wisdom that continues on to the realisations of the path and its primary purpose. Rather than feeling calm at the 4th stage of the second tetrad zandtao now looks for feeling love, using love to naturally control the vedanas - feeling calm then feeling love.

There is a possible patriarchal irony in Buddhadasa’s phraseology – mastering the vedanas could be taken to mean to be calm instead of loving. Loving has with it the power to change ie change patriarchy, calm has the ability to accept and could lead to bypassing; in a sense it could be said that patriarchy has mastered the vedanas changing them from love to calm.

Attached feelings do give rise to all the ahimsa actions Buddhadasa describes, but calming these feelings is in effect negating their power. What if these feelings were controlled by love – spiritual love (Buddhadasa's Dhamma love). Rather than acting in a detached way of calm we act in detached way of love - equanimity – wise loving. Whilst zandtao agrees with all that he has quoted from Buddhadasa, if spiritual love is absent then where is the power? Wisdom directs wisely but the power of love is the power to change. This is not the indiscriminate power of romantic love but the power of spiritual love that has wisdom as well as the power to change. There is a downside to this change. Calming the vedanas effectively removes their power and reduces the risk of attachment, with using love to control the vedanas there is power that needs controlling – a greater need for detachment. At times love has a tendency to become attached and not to be calm when we meet some of the ravages of ahimsa; whilst wisdom deals with this tendency not having this active power of love has left an imbalance in our world – an imbalance of less embodiment of love and love-wisdom.

For zandtaomed using love to feel, work with and control the vedanas is now part of his practice, work on the vedana leads to feeling love – not feeling calm. In zandtaomed’s teaching there would include the same stages in this tetrad as described by Buddhadasa’s MwB but they would lead to feeling love as mastering the vedanas - see zandtaomed autonomous practice.

In zandtaomed’s practice zandtaomed uses the love of the mother Gaia as Nicola does in this Divine Mother meditation. Through the stages of piti and sukka we learn of the power of the vedanas but instead of seeking calm alone we seek the mother’s love – Gaia’s love. As with Nicola’s meditation we bring the love of Gaia into our hearts and use it to control the vedanas. The 4th stage of the 2nd tetrad brings in Gaia’s love to feel love thus naturally controlling the vedanas with love.

In the 4 tetrads we then have the kaya conditioner – calming the body, and feeling love in the vedanas. The next tetrad is contemplating citta and is concerned with the development of wisdom. As we are already feeling love this increases the power of stage 9 where we develop compassion, metta, empathy and equanimity through the 4 brahma-viharas. Wisdom arises through the release of attachment during this 3rd tetrad, but love introduces deeper changes in the 4th tetrad – when reconnecting with Dhamma.

Stages 13 and 14 remain the same but in stage 15 zandtaomed now introduces an important embodiment stage; zandtaomed has taken approaches from Jac O’Keeffe’s embodiment meditation, but with significant differences. In her meditation Jac brings kindness into her heart, for zandtaomed love is there from the 2nd tetrad. Jac then develops spaciousness throughout her body to fill her body with love. Zandtaomed uses a similar method of spaciousness to integrate love-wisdom. Maintaining the love that was developed in the 2nd tetrad zandtaomed looks to create spaciousness in his body – releasing attachments. Then using the chakras (as does Jac) zandtaomed brings in love and wisdom to build up the ridgepole that Jac talks of. But zandtaomed introduces a step of integration so that the love and wisdom that is in the ridgepole is integrated into the spaciousness throughout the whole body – integrating the whole body with love and wisdom.

Previously zandtaomed has amended stage 15 to include interbeing so once the whole body has been integrated with love-wisdom, then that integration is expanded to interbeing.

So we come to stage 16 which leads to tathata. Bringing all the consciousness that has been released from stage 12 and any consciousness released from our work with vedanas we bring that consciousness together to have faith in the path – and then further so that we abide in the path. From this position of abidance we use our love and wisdom to see tathata. This is using a balance of love-wisdom and embodiment to feel, know and see the way things are – tathata. This advice is reflected in zandtaomed's practice described here

Through these changes in his practice zandtaomed has started to develop a love-wisdom balance.

|

Zandtao Meditation page

Zandtao Meditation page

Advice from Zandtaomed

Advice from Zandtaomed